.

#MyLai: @Seymour Hersh habla de la masacre que EEUU perpetró en 1968 y que él mismo denunció: image via Democracy Now! Es @DemocracyNowEs, 25 March 2015

Seymour Hersh: My Lai Revisited: excerpts from transcription of an interview, via Democracy Now!, 25 March 2015

If you remember, Richard Nixon came to office, defeated Humphrey in 1968. Humphrey would not go against the war, Lyndon Johnson’s war, his president’s war. He was the vice president. Nixon won by claiming he had a secret plan to end the war. And by the middle of 1969, or late 1969, it was clear his secret plan was to win it — not end it, but win it. And so, antiwar feelings were getting high. And I got a tip from — there were a lot of desertions, a lot of trouble inside the Army. Also, there were hearings and investigations, particularly one particular hearing in Detroit, Michigan, where a group of GIs, even a year earlier, 1968, had gone public with story after story of horrific incidents taking place. And I had read all those things. I was — you know, I guess I believe you can’t really write if you don’t read. And I knew how much there was an underbelly of very ugly stuff in that war that wasn’t being reported.

And so, when I got a tip in 1969, late 1969, I was a freelance writer. I had worked for the Associated Press, etc. And I had learned — I had covered the Pentagon for a few years and learned sort of OJT on how the war was being driven. Promotions in the war by 1966 and '67 were being driven by body count — how many could you kill? And inevitably, the officers and soldiers, eager to get more deaths, more killings, would stop differentiating in many areas, particularly the areas in Vietnam where My Lai took place — Quang Ngai, Quang Tri, Quang Nam — sort of areas known to be heavily engaged and committed to opposition to the South Vietnamese government. We called them Viet Cong. They weren't really — many of them were not communist, per se; they were nationalists against the war. But nonetheless, we carried the war — we were carrying the war very hard to them.

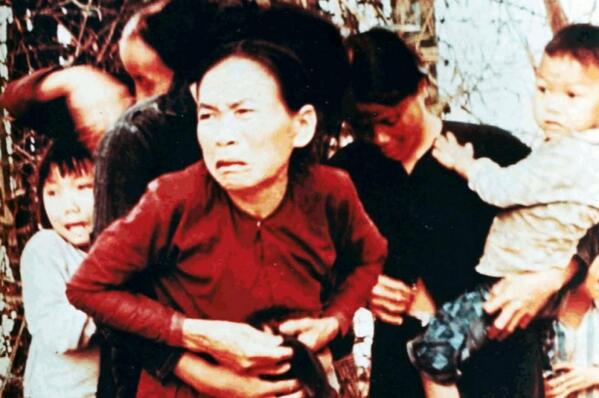

![File:MyLai Haeberle P33 BodiesNearBurningHouse.jpg]() Unidentified bodies near burning house. My Lai, Vietnam, March 16, 1968: photo by Sgt Ronald L. Ronald Haeberle, from Department of the Army Review of the Preliminary Investigations in the My Lai Incident; image by bcs78, 31 December 2006

Unidentified bodies near burning house. My Lai, Vietnam, March 16, 1968: photo by Sgt Ronald L. Ronald Haeberle, from Department of the Army Review of the Preliminary Investigations in the My Lai Incident; image by bcs78, 31 December 2006

So I knew all that. So when I got a tip from a lawyer, named Geoffrey Cowan, at the time, he was just involved in antiwar issues, working in Washington, that he had heard something about a massacre, I went looking. And there’s — you know, I was a soldier, I was in the Army, and I covered the Pentagon. And there is an enormous streak of decency and goodwill among many officers. And I’ve always — I always say this about the American intelligence community, too. Don’t write them off. There’s a lot of people with a lot of high integrity. And there was one day — I got nowhere on this story. And one day I was in the Pentagon, rolling around, I guess; I was going through the legal offices. The fact that officers had been detained by the Army on the suspicion of mass murder was not part of the record. I actually had run across Lieutenant Calley’s name, but I was told he was a — he had shot up a bunch of prostitutes in a bar in Saigon or something like that. Whoever told me that, that’s what he believed, that’s what he was told. But it wasn’t true. I didn’t know that.

And anyway, I ran into a colonel I knew, I had known when I was in the Pentagon earlier, who had just been promoted to general. And he was limping. He had been shot in the war. And I just started talking with him about it, teased him a little bit about taking a bullet to make general. You know, the black humor always is very big in the military. And then I said, "What’s this about some guy shooting up a lot of people?" And the colonel, soon to be a general, slammed his hand against his wounded knee, the knee in which he had a bullet while in Vietnam, and he said to me, "Oh, Hersh," he said, "that guy Calley didn’t shoot anybody higher than that." And at that moment, at that moment, I knew I had a story, that there was something there, something big. So I just kept on going.

I eventually found the name of Lieutenant Calley’s lawyer. I eventually got to the lawyer. I eventually got to Calley. And it was interesting, because I had heard so much about Calley. And I had actually seen by then a charge sheet accusing him. The Pentagon had initially accused him of something like 109 or 111, the killing of — get this — Oriental human beings. That was the initial charge sheet, as if 10 whites equaled one Oriental, or 12 blacks equaled one — I wasn’t sure what the number was. But believe me, they got rid of that as soon as I went public with that word. They took it out of the charge. It was a very interesting sort of notion, the notion of racism that’s so dominant in that war, as it is in all wars, I guess. You have to dehumanize the other person.

#OTD March 16 - 1968 #VietnamWar 450 @Men #Women and #Children die in the #MyLai #Massacre: image via Gerald McDonald @NovaRoma1, 16 March 2015

At the time of the massacre, this was going to be a big operation, and everybody thought, boy, we’re going to get — there was very bad intelligence. The intelligence was a Viet Cong battalion was there, the 48th, I think, and our boys were going to go in and kill them, and there was going to be a big ambush. And, of course, when we went in, there was nothing but women and children. The intelligence was lousy, as it always was. And they murdered everybody. They had been told to kill everybody you see. God knows what the real reality was, whether that was actually what — what happened, they went out of control, as they had many times before.

But, what I learned was that this was the big deal for the whole division. Charlie Company was attached to a task force, that was attached to a battalion, that was attached to a division. You know, we’re talking about 20,000 men, led by a major general named Koster. And that day, Koster, his deputy, another general named Young, a colonel who was in charge of the regiment to which the task force was attached, a battalion — colonels, generals, lieutenant colonels, majors were flying above, and I can just tell you from what I know, you had to understand, when you saw that village, with pits full of bodies, you knew there was something horrible that happened. They all knew it. They all covered it up. Actually, what they did is they reported to headquarters that that day had produced a great victory, that they had killed 128 Viet Cong with only three weapons captured — I mean, which was a flag in itself.

![Embedded image permalink]()

For Decades, the Media Have Ignored the #Rapes Behind a Famous Vietnam War Photo #myLai: image via Winter Thur @winterthur, 31 October 2013

They went in in the morning, a group of boys — and you’ve got to give them credit. You know, they toked the night before, and they did their whiskey the night before. They had their — you know, their drugs. But that morning, they got up thinking they were going to be in combat against the Viet Cong. They were happy to do it. Charlie Company had lost 20 people through snipers, etc. They wanted payback. And they had been taking it out on the people, but they had never seen the enemy. They’d been in country, as I said, in Vietnam for three or four months without ever having a set piece war. That’s just the way it is in guerrilla warfare — which is why we shouldn’t do it, but that’s another story. And they went in that morning ready to kill and be killed on behalf of America, to their credit. They landed. There were just nothing but women and children doing the usual, cooking, warming up rice for breakfast — and they began to put them in ditches and start executing them.

Calley’s company — Calley had a platoon. There were three platoons that went in. They rounded up people and put them in a ditch. And Meadlo was ordered by Calley. He was among one or two or three boys who did a lot of shooting. There was a big distinction, basically, between the white boys, country boys like Paul Meadlo who did the shooting, and the African Americans and Hispanics, who made up about 40 percent of the company. In my interviews, I found that distinction. Most of the African Americans and Hispanics, that was Whitey’s war. The whole thing was Whitey’s war for them. And they did shoot, because they were afraid that their white colleagues might shoot at them if they weren’t participating, but they shot high. One guy even shot himself in the foot to get out of there. I mean, we had that going on, too, above and beyond the normal stuff.

The other companies just went along, didn’t gather people, just went from house to house and killed and raped and mutilated, and had just went on until everybody was either run away or killed. Four hundred and some-odd people in that village alone, of the 500 or 600 people who lived there, were murdered that day, all by noon, 1:00.

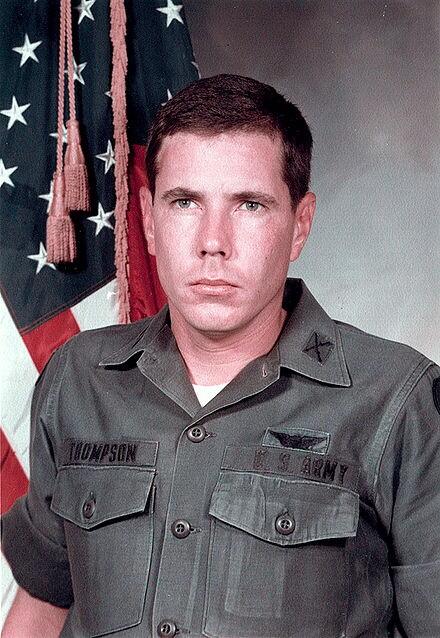

On 1 of the darkest days in US history, Hugh Thompson, Jr was a hero. He would've been 71 today. #myLai: image via Brent Scales @Boiler40, 15 April 2014 At one point, one helicopter pilot, a wonderful man named Thompson, saw what was going on and actually landed his helicopter. He was a small combat — had two gunners. He just landed his small helicopter, and he ordered his gunners to train their weapons on Lieutenant Calley and other Americans. And Calley was in the process of — apparently going to throw hand grenades into a ditch where there were 10 or so Vietnamese civilians. And he put his guns on Calley and took the civilians, made a couple trips and took them out, flew them out to safety. He, of course, was immediately in trouble for doing that.

It was just the instinct to not do the right thing. You know, the thing that you discovered about Vietnam was, there was no such thing as a war crime. It just didn’t exist. The idea of a war crime didn’t exist. There were violations of rules and things you did wrong. And one of things that emerged in Vietnam — a defense to, let’s say, rape — would have been what they called the MGR, the Mere Gook Rule: It was just a gook. I’m not exaggerating. It was that terrible, that racist. You talk about number of deaths in Iraq, and the number is staggering, but we usually talk in Vietnam — we don’t get within — we talk — is it one or two or three million civilians and innocents killed between the North and the South?

Photo: Guerre du Vietnam, le Massacre de My Lai #myLai #vietnam #guerreduvietnam: image via Forum Vietnam @ForumVietnam, 25 March 2015

[Paul Meadlo] and another soldier from Texas had been asked by Calley — they had no idea what Calley’s intent was. Paul Meadlo was a kid. You know, he had been married young. He was from New Goshen, Indiana, from a farm family. His father worked in the mines on the border with Illinois. And they were very close to the border in New Goshen, near Terre Haute. He was a farm kid, into the Army, trained to be a killer. His brother told me when I was doing interviews for this piece — I talked to his brother, Larry, who lives near him, and said Paul was the — he couldn’t skin an animal after shooting them when hunting. He didn’t like the sight of blood. The last person that should have been drafted, but he was drafted, and he went.

And that morning, Calley ordered Meadlo and others to collect a group of women and children. They had 40 or 50, perhaps more, some old men, mostly women and kids. And Paul and the other guys, Calley said to watch them. And so they did what kids, American guys, will do: They passed out candy. They were horsing around with the kids, playing with the kids. They told the people where to sit. And Calley came back and said, you know, in effect, "What are you doing?" He said, "I told you to take care of them." He said, "Well, I am." He said, "No, I want them killed."

La companie #US #CHARLIE a massacré #MYLAI au #Vietnam le 16 mars 1968! #USA #URSS #Russie: image via Claire - Normans @Slava_Russia72, 1 March 2015

And then Meadlo began following orders. He began crying. This is something I did not know until I revisited some of the investigations. I went and reread everything that the Army had done. I just had not read it all before. And I found other witnesses who testified at Army hearings. After my stories came out, there was a big investigation by a general named Peers. And there was another soldier, a New York kid. Naturally, a New York street kid wasn’t going to shoot, but he watched what happened. He testified about Meadlo beginning to cry. He didn’t want to do it, and Calley ordered him to. And he began to shoot and shoot. And they fired clips — I don’t know how many clips; he told me at one point five or six; he testified later about one, but he told me four, maybe five, clips — a clip in that rifle, an M1, has 17 bullets — into it, into the ditch.

And there was a horrible moment that got me, really got me. At some point, when they were done shooting, some mother had protected a baby underneath her body in the bottom of the ditch. And the GIs heard, as somebody said to me, a keening, a crying, whimpering noise, and a little two- or three-year-old boy crawled his way out full of other people’s blood from the ditch. It’s hard for me to talk about this. And right across what was — it’s now been plowed over, but it was a rice ditch. It’s now been paved over at the site. And I saw it all. I’d seen it in my mind, and I saw it visually that day I was there. And the kid was running away, and Calley went after it — Calley, big, tough guy with his rifle — and dragged him, grabbed him, dragged him back into the ditch and shot him. And that stuck in people’s minds.

#Taldíacomohoy de 1970, #EEUU, Guerra #Vietnam, teniente William Calley va a juicio por ordenar la masacre de #MyLai: image via Red Communismor @RedCommunismo, 17 November 2014

That’s how I got to Calley. It was a repressed memory, what happened at that ditch. And as I was doing my interviews early in the story — I had written two stories for Dispatch. And the press, I will tell you, the American press, was — they were open to the story. They didn’t really get into it. They let me sort of run with it for weeks. It made me think, as I still do, that you can really do stuff if you want to do stuff. The American press, they may not be aggressive, but if you do stuff that they think is right, they will publish it. I’d like to think that’s still true. I mean, it happened in Abu Ghraib, and it happened in other stories I’ve written. There’s a lot of resistance to stories sometimes, but not in this case. It just seemed right. And anyway, soldiers had told me — finally, they told me about Paul Meadlo. And as I wrote in the piece, I was in Salt Lake City at the time I heard about him and what he did and what happened. I didn’t hear about crying, but I heard about his resistance and about the little boy. And I spent hours on a payphone. His name was M-E-A-D-L-O, and I knew he lived in Indiana. I called every major phone district, city, and got the chief operator and asked for Meadlo, finally found him.

And I asked — I got the house, and I called the house in New Goshen. And I asked — I knew he had had his — the next day, Paul Meadlo had had his leg blown off by stepping on a mine. And he kept on saying — as he was waiting for the helicopter to take him to a hospital, he kept on yelling at Calley, "God is punishing me! And God will get you, B! God will get you for this!" And they finally took him away. So, when I called his home, and I would ask — I got this woman, this old Southern voice, and I said, "Is Paul there?" And she said, "Yes," which was great. And I said, "How is his leg?" She says, "Well, you know, I don’t know." And I asked if I could see him. She said, "Yes. Ask him." She didn’t know. She didn’t know much about what happened. She knew something bad had happened. And I flew down there.

And I went — it took me a long time to get to New Goshen, Indiana. No GPS then. I mean, I flew across country all night, but I got there by afternoon to this little rinkety-dinkety farm full of — a farm with no man around, full of chickens, that were — chicken coops that were broken down. But she came out to meet me. And this is one of those moments you live for as a journalist, I guess. This woman, who really wasn’t really in the world, didn’t know much about what was going on. Paul hadn’t told her much. She came out to meet me, and I pulled in 3:00 or 4:00 in the afternoon. And I said, "I’m the"— I told her I was a reporter, and I said, "I’ve come to see Paul. Is he in?" She said, "He’s in there." She said, "I don’t know if he’ll talk to you, but he’s in there. He knows you’re coming." And then she said to me, this old woman, she said, in this tone of a voice, "I gave them a good boy, and they sent me back a murderer." And you can go a long time in this business without having a line like that played in your head.

#MyLai one of many examples of the "#freedom and #democracy" our NATO EU régimes, South Korea, Taiwan, Saigon love: image via @VivaSAA Rafiq @Rafiq_al_Taneen, 29 April 2014

![Thistle in September Thistle in September]()

![Tomatoes in September Tomatoes in September]()

![Day Lilys on Cottonwood Day Lilys on Cottonwood]()

![Artichokes on the rue Madame Artichokes on the rue Madame]()