.

Donnybrook, Dublin: photo by Fergus O'Connor, c. 1920 (Fergus O'Connor Collection, National Library of Ireland)

Donnybrook, Dublin: photo by Fergus O'Connor, c. 1920 (Fergus O'Connor Collection, National Library of Ireland)

Horse trams at corner of Bachelor's Walk and O'Connell Bridge [Dublin]: photo by Robert French, c. 1897 (Lawrence Photographic Collection, National Library of Ireland)

The most trivial experience -- he says in effect -- is encrusted with elements that logically are not related to it and have consequently been rejected by our intelligence: it is imprisoned in a vase filled with a certain perfume and a certain colour and raised to a certain temperature. These vases are suspended along the height of our years, and, not being accessible to our intelligent memory, are in a sense immune, the purity of their climatic content is guaranteed by forgetfulness, each one is kept at its distance, at its date. So that when the imprisoned microcosm is besieged in the manner described, we are flooded by a new air and a new perfume (new precisely because already experienced), and we breathe the true air of Paradise, of the only Paradise that is not the dream of a madman, the Paradise that has been lost.

Long Room Library, Trinity College, Dublin: photo by Robert French, c. 1885 (Lawrence Photographic Collection, National Library of Ireland)

But if this mystical experience communicates an extratemporal essence, it follows that the communicant is for the moment an extratemporal being. Consequently the Proustian solution consists, in so far as it has been examined, in the negation of Time and Death, the negation of Death because the negation of Time. Death is dead because Time is dead. (At this point a brief impertinence, which consists in considering Le Temps Retrouvé almost as inappropriate a description of the Proustian solution as Crime and Punishment of a masterpiece that contains no allusion to either crime or punishment. Time is not recovered, it is obliterated. Time is recovered, and Death with it, when he leaves the library and joins the guests, perched in precarious decrepitude on the aspiring stilts of the former and preserved from the latter by a miracle of terrified equilibrium. If the title is a good title the scene in the library is an anticlimax.)

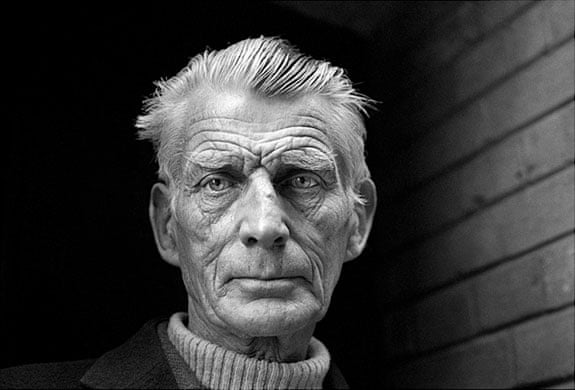

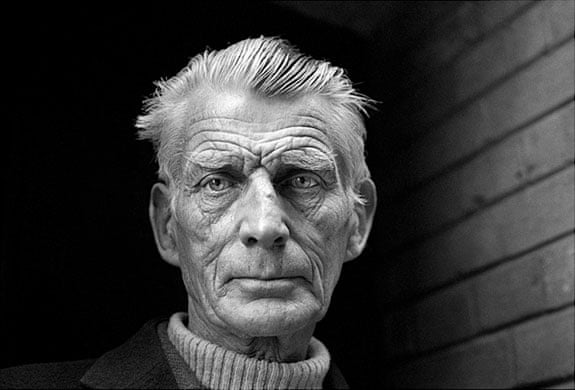

Samuel Beckett (b. Dublin 1906-d. Paris 1989): on involuntary memory: from Proust (1931)

Dublin street scene: photographer unknown, c. 1912 (Eason Collection. National Library of Ireland)

Dublin street scene: photographer unknown, c. 1912 (Eason Collection. National Library of Ireland)

Samuel Beckett. Pictured leaving the Royal Court Theatre, Sloane Square, London, via the stage door, after rehearsals of Happy Days starring Billie Whitelaw, as part of the Beckett season to celebrate his 70th birthday. April 1976: photo by Jane Bown (1925-2014) for The Observer via The Guardian, 17 October 2009

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Samuel Beckett. Pictured leaving the Royal Court Theatre, Sloane Square, London, via the stage door, after rehearsals of Happy Days starring Billie Whitelaw, as part of the Beckett season to celebrate his 70th birthday. April 1976: photo by Jane Bown (1925-2014) for The Observer via The Guardian, 17 October 2009

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Donnybrook, Dublin: photo by Fergus O'Connor, c. 1920 (Fergus O'Connor Collection, National Library of Ireland)

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Donnybrook, Dublin: photo by Fergus O'Connor, c. 1920 (Fergus O'Connor Collection, National Library of Ireland)

The most successful evocative experiment can only project the echo of a past sensation, because, being an act of intellection,it is conditioned by the prejudices of the intelligence which abstracts from any given sensation, as being illogical and insignificant, a discordant and frivolous intruder, whatever word or gesture, sound or perfume, cannot be fitted into the puzzle of a concept. But the essence of any new experience is contained precisely in this mysterious element that the vigilant will reject as an anachronism. It is the axis about which the sensation pivots, the centre of gravity of its coherence. So that no amount of voluntary manipulation can reconstitute in its integrity an impression that the will has -- so to speak -- buckled into incoherence. But if, by accident, and given favourable circumstances (a relaxation of the subject’s habit of thought and a reduction of the radius of his memory, a generally diminished tension of consciousness following upon a phase of extreme discouragement), if by some miracle of analogy the central impression of a past sensation recurs as an immediate stimulus which can be instinctively identified by the subject with the model of duplication (whose integral purity has been retained because it has been forgotten), then the total past sensation, not its echo nor its copy, but the sensation itself, annihilating every spatial and temporal restriction, comes in a rush to engulf the subject in all the beauty of its infallible proportion.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Horse trams at corner of Bachelor's Walk and O'Connell Bridge [Dublin]: photo by Robert French, c. 1897 (Lawrence Photographic Collection, National Library of Ireland)

The most trivial experience -- he says in effect -- is encrusted with elements that logically are not related to it and have consequently been rejected by our intelligence: it is imprisoned in a vase filled with a certain perfume and a certain colour and raised to a certain temperature. These vases are suspended along the height of our years, and, not being accessible to our intelligent memory, are in a sense immune, the purity of their climatic content is guaranteed by forgetfulness, each one is kept at its distance, at its date. So that when the imprisoned microcosm is besieged in the manner described, we are flooded by a new air and a new perfume (new precisely because already experienced), and we breathe the true air of Paradise, of the only Paradise that is not the dream of a madman, the Paradise that has been lost.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Long Room Library, Trinity College, Dublin: photo by Robert French, c. 1885 (Lawrence Photographic Collection, National Library of Ireland)

But if this mystical experience communicates an extratemporal essence, it follows that the communicant is for the moment an extratemporal being. Consequently the Proustian solution consists, in so far as it has been examined, in the negation of Time and Death, the negation of Death because the negation of Time. Death is dead because Time is dead. (At this point a brief impertinence, which consists in considering Le Temps Retrouvé almost as inappropriate a description of the Proustian solution as Crime and Punishment of a masterpiece that contains no allusion to either crime or punishment. Time is not recovered, it is obliterated. Time is recovered, and Death with it, when he leaves the library and joins the guests, perched in precarious decrepitude on the aspiring stilts of the former and preserved from the latter by a miracle of terrified equilibrium. If the title is a good title the scene in the library is an anticlimax.)

Samuel Beckett (b. Dublin 1906-d. Paris 1989): on involuntary memory: from Proust (1931)

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Dublin street scene: photographer unknown, c. 1912 (Eason Collection. National Library of Ireland)

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Westland Row? Absolutely not! | by National Library of Ireland on The Commons]()

Clik here to view.

Dublin street scene: photographer unknown, c. 1912 (Eason Collection. National Library of Ireland)

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Clik here to view.

Samuel Beckett. Pictured leaving the Royal Court Theatre, Sloane Square, London, via the stage door, after rehearsals of Happy Days starring Billie Whitelaw, as part of the Beckett season to celebrate his 70th birthday. April 1976: photo by Jane Bown (1925-2014) for The Observer via The Guardian, 17 October 2009

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Samuel Beckett. Pictured leaving the Royal Court Theatre, Sloane Square, London, via the stage door, after rehearsals of Happy Days starring Billie Whitelaw, as part of the Beckett season to celebrate his 70th birthday. April 1976: photo by Jane Bown (1925-2014) for The Observer via The Guardian, 17 October 2009

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Clik here to view.

Tuol Sleng genocide museum, Cambodia: photo by Ambroise Tézenas via the Guardian, 13 November 2014

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Tuol Sleng genocide museum, Cambodia: photo by Ambroise Tézenas via the Guardian, 13 November 2014

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Bottles and vases: Pietro Bigaglia, c. 1845, glassware (Museo del Vetro, Murano)

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Bottles and vases: Pietro Bigaglia, c. 1845, glassware (Museo del Vetro, Murano)