.

![]()

Iranian carpet salesmen watching an announcement of the nuclear pact Iran reached with six nations and the European Union, an agreement negotiated by the United States. The deal will end international oil and financial sanctions in return for limits on Iran’s nuclear production and fuel stockpile over the next 15 years: photo by Arash Khamooshi for The New York Times 14 July 2015

Joseph Ceravolo: Complaint

Have no social complaints

Not to the rich, not to the poor,

![]()

![]()

An Iranian coal miner pushes a metal cart loaded with coal at a mine near the city of Zirab 212 kilometers (132 miles) northeast of the capital Tehran, on a mountain in Mazandaran province. The miners move up to 100 tons of coal a day: photo by Ebrahim Noroozi/AP. 18 August 2014

![]()

![]()

An Iranian coal miner works inside a mine near the city of Zirab 212 kilometers (132 miles) northeast of the capital Tehran, on a mountain in Mazandaran province. The miners tunnel deep into the mountains, working in dark, narrow passageways where the risk of toxic gases and cave-ins is never far from their minds: photo by Ebrahim Noroozi/AP. 18 August 2014

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Angela Merkel, the German chancellor, visiting Infineon Technologies in Dresden, part of a tour of the German microelectronics industry. Infineon employs about 2,000 people in its Dresden factory, where it makes semiconductors: photo by Arno Burgi/Reuters via New York Times, 14 July 2015

![]()

![]()

Imam (formerly Shah) Mosque (Masjed-e Imam), Isfahan: photo by Dara Mulhern, 18 October 2010

![]()

Main Dome, Imam (formerly Shah) Mosque (Masjed-e Imam), Isfahan (1611-1629}: photo by Dara Mulhern, 18 October 2010

![]()

Side Dome, Imam (formerly Shah) Mosque (Masjed-e Imam), Isfahan: photo by Dara Mulhern, 18 October 2010

![]()

Imam (formerly Shah) Mosque, Isfahan: photo by HORIZON, 18 May 2006

![]()

Sheikh Lotf Allah Mosque, Isfahan: photo by oceanbaby, 4 May 2007

![]()

Sheikh Lotf Allah Mosque, Isfahan: photo by Behrooz Bashokooh, 15 March 2011

![]()

Muqarnas, Sheikh Lotf Allah Mosque, Isfahan: photo by Mandana Fard (baraneh), 8 January 2008

![]()

Iranian carpet salesmen watching an announcement of the nuclear pact Iran reached with six nations and the European Union, an agreement negotiated by the United States. The deal will end international oil and financial sanctions in return for limits on Iran’s nuclear production and fuel stockpile over the next 15 years: photo by Arash Khamooshi for The New York Times 14 July 2015

Iranian carpet salesmen watching an announcement of the nuclear pact Iran reached with six nations and the European Union, an agreement negotiated by the United States. The deal will end international oil and financial sanctions in return for limits on Iran’s nuclear production and fuel stockpile over the next 15 years: photo by Arash Khamooshi for The New York Times 14 July 2015

Joseph Ceravolo: Complaint

Have no social complaints

have no god complaints

was born a beggar

was born a beggar

live a beggar.

I have no complaints.

I have no complaints to the moon,

none to the stars,

none to the astrology of the mind,

none to the liars of religious words

or to the doom prophets

on the edges of truth.

Have no complaints.

Not to the rich, not to the poor,

not to the powerful, not to

the weak. I only ask for a little grace,

a tear here and there

shed for the brotherhood of man and woman,

not for me.

I have no complaints.

..............................

Joseph Ceravolo (1934-1988): Complaint, 27 August 1986, from Collected Poems, 2012

..............................

Joseph Ceravolo (1934-1988): Complaint, 27 August 1986, from Collected Poems, 2012

Iranians take to Tehran streets to hail nuclear #IranDeal: image by Agence France-Presse @AFP, 14 July 2015

Iranian coal miners eat lunch at a mine near the city of Zirab 212 kilometers (132 miles) northeast of the capital Tehran, on a mountain in Mazandaran province. International sanctions linked to the decade-long dispute over Iran’s nuclear program have hindered the import of heavy machinery and modern technology in all sectors, and coal mining is no exception. The decision to privatize the industry 10 years ago has further squeezed miners, who work often in dangerous conditions -- and make just $300 a month, little more than minimum wage: photo by Ebrahim Noroozi/AP. 19 August 2014

An Iranian coal miner pushes a metal cart loaded with coal at a mine near the city of Zirab 212 kilometers (132 miles) northeast of the capital Tehran, on a mountain in Mazandaran province. The miners move up to 100 tons of coal a day: photo by Ebrahim Noroozi/AP. 18 August 2014

Iranian coal miners pose for a photograph at a mine on a mountain in Mazandaran province, near the city of Zirab 212 kilometers (132 miles) northeast of the capital Tehran. International sanctions linked to the decade-long dispute over Iran’s nuclear program have hindered the import of heavy machinery and modern technology in all sectors, and coal mining is no exception. The decision to privatize the industry 10 years ago has further squeezed miners, who work often in dangerous conditions -- and make just $300 a month: photo by Ebrahim Noroozi/AP, 18 August 2014

An Iranian coal miner works inside a mine near the city of Zirab 212 kilometers (132 miles) northeast of the capital Tehran, on a mountain in Mazandaran province. The miners tunnel deep into the mountains, working in dark, narrow passageways where the risk of toxic gases and cave-ins is never far from their minds: photo by Ebrahim Noroozi/AP. 18 August 2014

An Iranian coal miner pushes an old metal cart to be loaded with coal at a mine near the city of Zirab 212 kilometers (132 miles) northeast of the capital Tehran on a mountain in Mazandaran province. A miner said they move up to 100 tons a day: photo by Ebrahim Noroozi/AP, 8 May 2014

An Iranian coal miner takes a break at a mine near the city of Zirab 212 kilometers (132 miles) northeast of the capital Tehran, on a mountain in Mazandaran province. International sanctions linked to the decade-long dispute over Iran’s nuclear program have hindered the import of heavy machinery and modern technology in all sectors, and coal mining is no exception. The decision to privatize the industry 10 years ago has further squeezed miners, who work often in dangerous conditions -- and make just $300 a month, little more than minimum wage: photo by Ebrahim Noroozi/AP. 8 May 2014

Iranian coal miners rest during a break at a mine on a mountain in Mazandaran province, near the city of Zirab, 212 kilometers (132 miles) northeast of the capital Tehran. The miners put in long hours in often dangerous conditions and make just $300 a month, little more than minimum wage: photo by Ebrahim Noroozi/AP. 6 May 2014

Iranian coal miners pose for a photograph before taking a shower after a long day of work at a mine on a mountain in Mazandaran province, near the city of Zirab 212 kilometers (132 miles) northeast of the capital Tehran. The miners put in long hours in often dangerous conditions making just $300 a month, little more than minimum wage: photo by Ebrahim Noroozi/AP. 7 May 20144

An Iranian coal miner takes a shower while others prepare to go home after a long day of work at a mine on a mountain in Mazandaran province, near the city of Zirab, 212 kilometers (132 miles) northeast of the capital Tehran. Around 1,200 miners work across 10 mines in the Mazandaran province, in a mountainous, verdant area. More than 12,000 tons of coal is extracted from the mines each month, almost all of which is shipped south for use in Iran’s steel industry: photo by Ebrahim Noroozi/AP. 6 May 2014

Angela Merkel, the German chancellor, visiting Infineon Technologies in Dresden, part of a tour of the German microelectronics industry. Infineon employs about 2,000 people in its Dresden factory, where it makes semiconductors: photo by Arno Burgi/Reuters via New York Times, 14 July 2015

The conventional view holds that girih (geometric star-and-polygon, or strapwork) patterns in medieval Islamic architecture were conceived by their designers as a network of zigzagging lines, where the lines were drafted directly with a straightedge and a compass. We show that by 1200 C.E. a conceptual breakthrough occurred in which girih patterns were reconceived as tessellations of a special set of equilateral polygons ("girih tiles") decorated with lines. These tiles enabled the creation of increasingly complex periodic girih patterns, and by the 15th century, the tessellation approach was combined with self-similar transformations to construct nearly perfect quasi-crystalline Penrose patterns, five centuries before their discovery in the West.

Decagonal and Quasi-Crystalline Tilings in Medieval Islamic Architecture, by Peter J. Lu and Paul J. Steinhardt: abstract of a paper in Science 23, February 2007, Vol. 315. no. 5815

![]()

![]()

Decagonal and Quasi-Crystalline Tilings in Medieval Islamic Architecture, by Peter J. Lu and Paul J. Steinhardt: abstract of a paper in Science 23, February 2007, Vol. 315. no. 5815

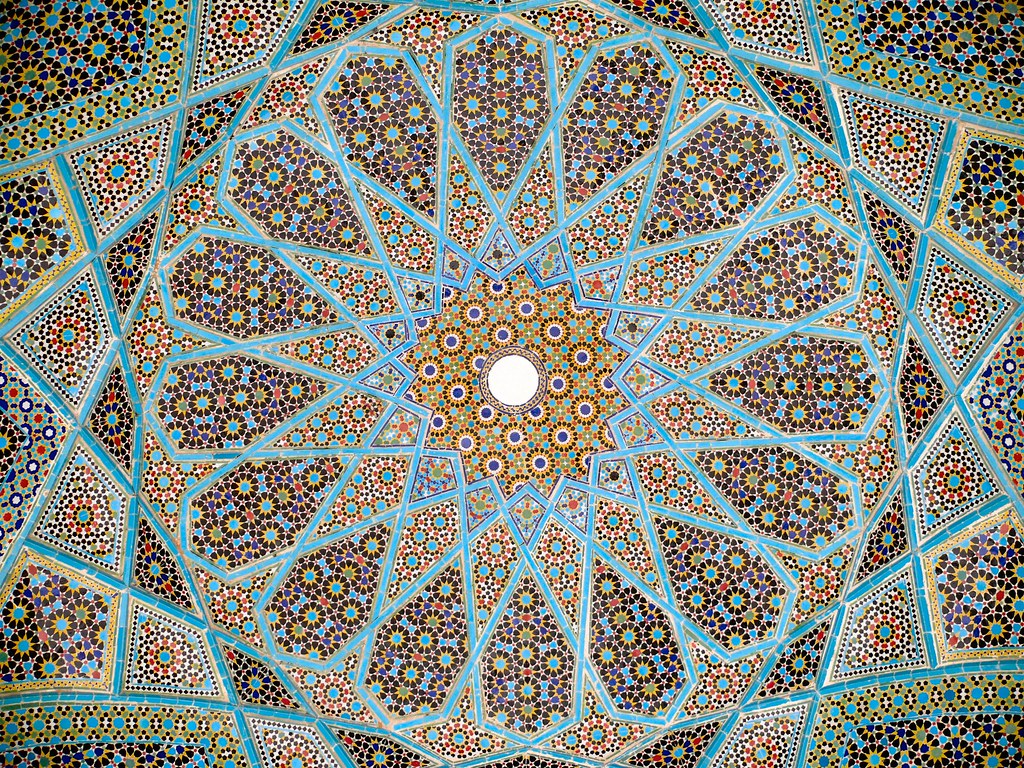

A glance at heaven: vault at the Nasr ol Molk mosque, Shiraz: photo by dynamomosquito, 2008

Another glance at heaven: vault at the Nasr ol Molk mosque, Shiraz: photo by dyanamomosquito, 2007

For all their tantalizing glimpses into medieval scientific knowledge, the designs of the Darb-i Imam [in Isfahan, taken by Peter Lu as a template for his thesis] and other Islamic buildings must also be understood in their religious context. Geometric patterns in Islamic architecture and ornamentation were used as much for spiritual as for artistic reasons. As Robert Irwin writes in his study of Islamic art, such patterns may have been viewed 'as exteriorized representations of abstract, even mystical, thought' -- aiming to inspire contemplation or to make a statement about the imponderable harmonies of a divinely ordered universe. Sufism in particular is closely linked to the practice of geometry, above all in the form of symmetries, as a way of giving physical expression to mystical thought.

The girih designs are thus comparable to Gothic art and architecture in another sense, namely in their shared ambition to embody spiritual cogitation and emotion through geometry. The real significance of the magnificent tiling of the Darb-i Imam lies not in any kind of cultural one-upmanship about who first conceived a certain idea or technique, but rather in the remarkable trajectories of ideas and scientific endeavors through time.

Sebastian R. Prange, on the Lu thesis, in Islamic Arts and Architecture, 20 May 2012

Eternity: ceramic tile mosaic, roof of the tomb of Persian poet Hafez, province of Fars, 2008: photo by dynamomosquito, 2008

Imam (formerly Shah) Mosque (Masjed-e Imam), Isfahan: photo by Dara Mulhern, 18 October 2010

Main Dome, Imam (formerly Shah) Mosque (Masjed-e Imam), Isfahan (1611-1629}: photo by Dara Mulhern, 18 October 2010

Side Dome, Imam (formerly Shah) Mosque (Masjed-e Imam), Isfahan: photo by Dara Mulhern, 18 October 2010

Imam (formerly Shah) Mosque, Isfahan: photo by HORIZON, 18 May 2006

Sheikh Lotf Allah Mosque, Isfahan: photo by oceanbaby, 4 May 2007

Sheikh Lotf Allah Mosque, Isfahan: photo by Behrooz Bashokooh, 15 March 2011

Muqarnas, Sheikh Lotf Allah Mosque, Isfahan: photo by Mandana Fard (baraneh), 8 January 2008

Iranian carpet salesmen watching an announcement of the nuclear pact Iran reached with six nations and the European Union, an agreement negotiated by the United States. The deal will end international oil and financial sanctions in return for limits on Iran’s nuclear production and fuel stockpile over the next 15 years: photo by Arash Khamooshi for The New York Times 14 July 2015