.

Circus sideshow billboards, Santa Monica, California: photo by Walker Evans, August-September 1967 (Walker Evans Archive/Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Feeling the way I did, alone and friendless, with the future very black, I did not want to get out on the streets and see what the sun had to show me, a cheap town filled with cheap stores and cheap people, like the town I had left, identically like any one of ten thousand other small towns in the country -– not my Hollywood, not the Hollywood you read about. This is what I was afraid of now, I did not want to take a chance on seeing anything that might have made me wish I had stayed home, and this is why I had waited for the darkness, for the night-time. That is when Hollywood is really glamorous and mysterious and you are glad you are here, where miracles are happening all around you, where today you are broke and unknown and tomorrow you will be rich and famous. . . .

On Vine Street I went north towards Hollywood Boulevard, crossing Sunset, passing the drive-in stand where the old Paramount lot used to be, seeing young girls and boys in uniform hopping cars and seeing, too, in my mind, the ironic smiles on the faces of Wallace Reid and Valentino and all the other old-time stars who used to work on this very spot, and who now looked down, pitying these girls and boys for working at jobs in Hollywood they might just as well be working at in Waxahachie or Evanston or Albany; thinking if they were going to do this, there was no point in their coming out here in the first place.

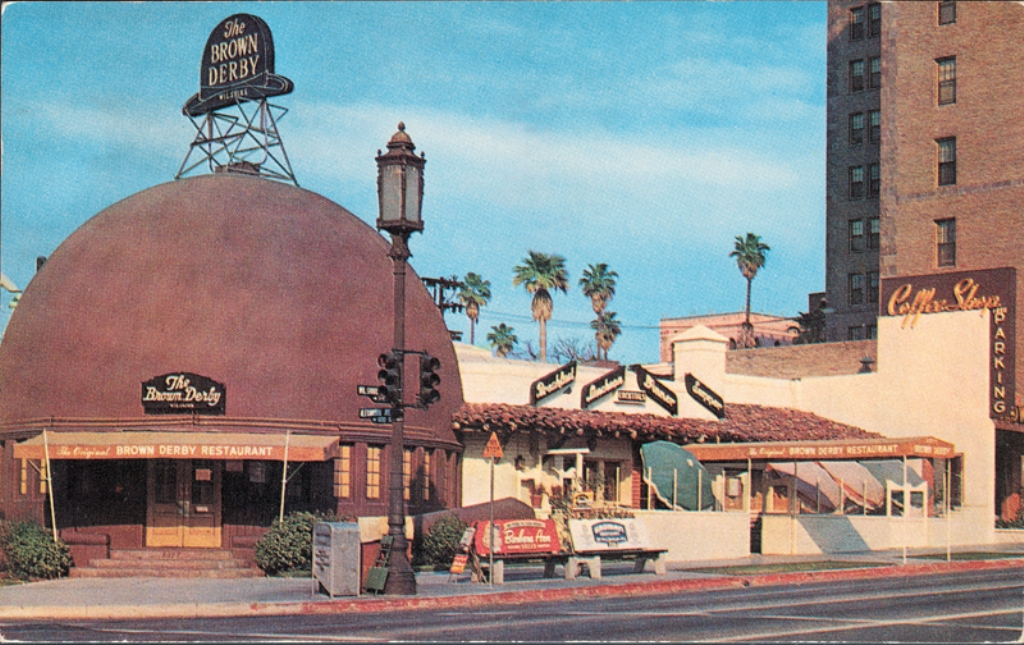

THE BROWN DERBY, the sign said, and I crossed the street, not wanting to pass directly in front, hating the place and all the celebrities in it (only because they were celebrities, something I was not), hating the people standing in front thinking: You'll be fighting for my autograph one of these days...

*

That night I discovered the park at De Longpre and Cherokee. I was walking around the streets in the neighborhood, Fountain and Livingston and Cahuenga, because they were dark and lonely, looking at all the small houses, telling myself that these were where Swanson and Pickford and Chaplin and Arbuckle and the others used to live in the good old days and what a shame it was they had to pass, feeling a personal loss that was still very warm and nostalgic, like a visit to a graveyard where your grandfather and grandmother and all your relatives are buried. You don't feel that you are a stranger even though you have never visited the graveyard before because the tombstones represent something and somebody you have known a long, long time, and loved, and it was like that now. I was no stranger on these streets. . . .

I came upon the park suddenly. At first I thought it was the yard of some house, because you don't expect a city park to be as small as this one was; it covered only half a block. But when I saw the benches around and the sign telling you to keep off the grass, I knew what it was. I sat down on a wet bench and looked around. There was nobody else there, which was right and proper. It was still misting a little, and all the other fools were inside their little houses.

There was a red haze above the boulevard eight blocks north, thrown up by the neon signs. The only building you could see over the tops of the small houses was the Catholic church on Sunset, its white spire sticking straight up into the black sky.

Presently I was aware that there was someone else in the park. I looked around, behind me, and saw a figure silhouetted in light from the single globe that was fixed on top of some kind of grass shelter. I couldn't tell whether it was a man or a woman. It was on its knees, in front of a small fountain, in an attitude of prayer, its hands moving rapidly in some kind of Oriental gesture. This continued for a few minutes and then the figure got up and walked past me out of the park. It was a woman, a middle-aged woman, dressed entirely in black.

I walked over to the fountain. It was a fish-pond and what I had thought was a fountain was a statue. The statue was about three feet high, a figure with arms at its side, its head lifted. I leaned forward, looking at the tablet.

ASPIRATION

Erected in memory of Rudolph

Valentino

1895.....................1926

1895.....................1926

Presented by his friends and

admirers from every walk of

life -- in all parts of the world

in appreciation of the Happiness

brought to them by his

cinema portrayals.

admirers from every walk of

life -- in all parts of the world

in appreciation of the Happiness

brought to them by his

cinema portrayals.

On the railing around the pond, in front to the statue, was the single gardenia the woman had left.

"I know how you feel, lady," I said to her in my mind. "I know exactly how you feel. . . ."

Horace McCoy (1897-1955): from I Should Have Stayed Home, 1938

![http://memory.loc.gov/service/pnp/cph/3c30000/3c31000/3c31600/3c31699v.jpg]()

Young woman standing on sidewalk with suitcase, Hollywood, California: photo by Russell Lee, April 1942 (Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Collection, Library of Congress)

Young woman standing on sidewalk with suitcase, Hollywood, California: photo by Russell Lee, April 1942 (Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Collection, Library of Congress)

The Brown Derby, Wilshire and Alexandria, Los Angeles: postcard, photographer unknown, c. 1955 (James Rojas Collection, Dorothy Peyton Gray Transportation Library and Archive)

The original Brown Derby, Wilshire Boulevard, Los Angeles: photo by Chalmers Butterfield, n.d.; image by liftarn, 14 August 2007

Rudolph Valentino Aspiration Statue, De Longpre Park, Hollywood: photo by mercycube, 4 October 2008

Rudolph Valentino Aspiration Statue, De Longpre Park, Hollywood: photo by mercycube, 4 October 2008

Rudolph Valentino Aspiration Statue, De Longpre Park, Hollywood: photo by mercycube, 4 October 2008

Rudolph Valentino Aspiration Statue, De Longpre Park, Hollywood: photo by mercycube, 4 October 2008

De Longpre Park, Hollywood: photo by mercycube, 4 October 2008

View of the (almost) Harvest Moon, Observatory and Hollywood sign above Runyon: photo by julie neumann, 22 October 2012

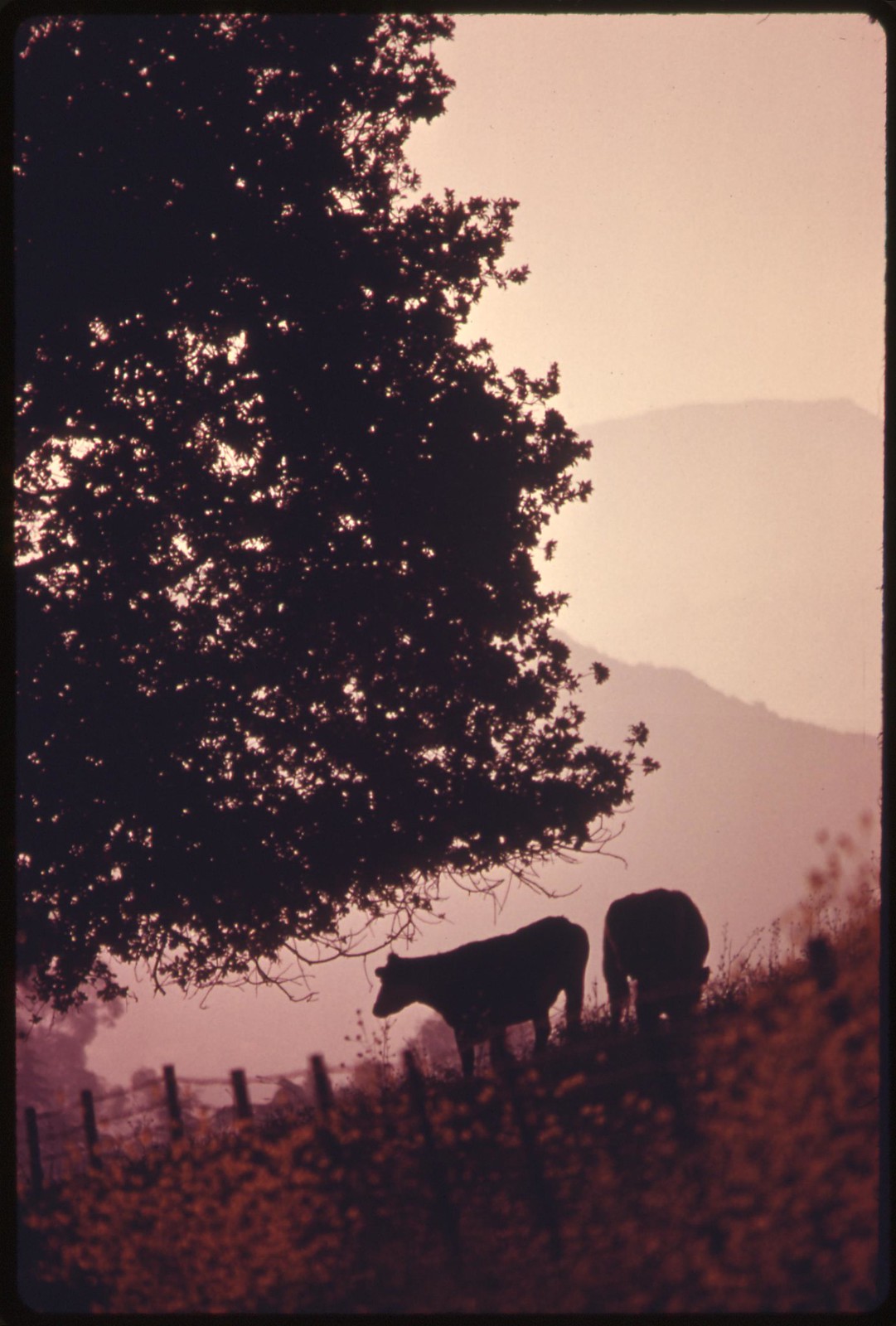

Bucolic scene along Mulholland Drive in the Santa Monica Mountains on the western edge of Los Angeles. The mountains contain the last semi-wilderness in Los Angeles County. Some 84 percent of the state's residents live within 30 miles of the coast, and this concentration has resulted in increased land use pressure. Of the 1,072 miles of mainland shoreline (excluding San Francisco Bay) 61 percent is privately owned: photo by Charles O'Rear for the Environmental Protection Agency's Documerica Project, May 1975 (US National Archives)