.

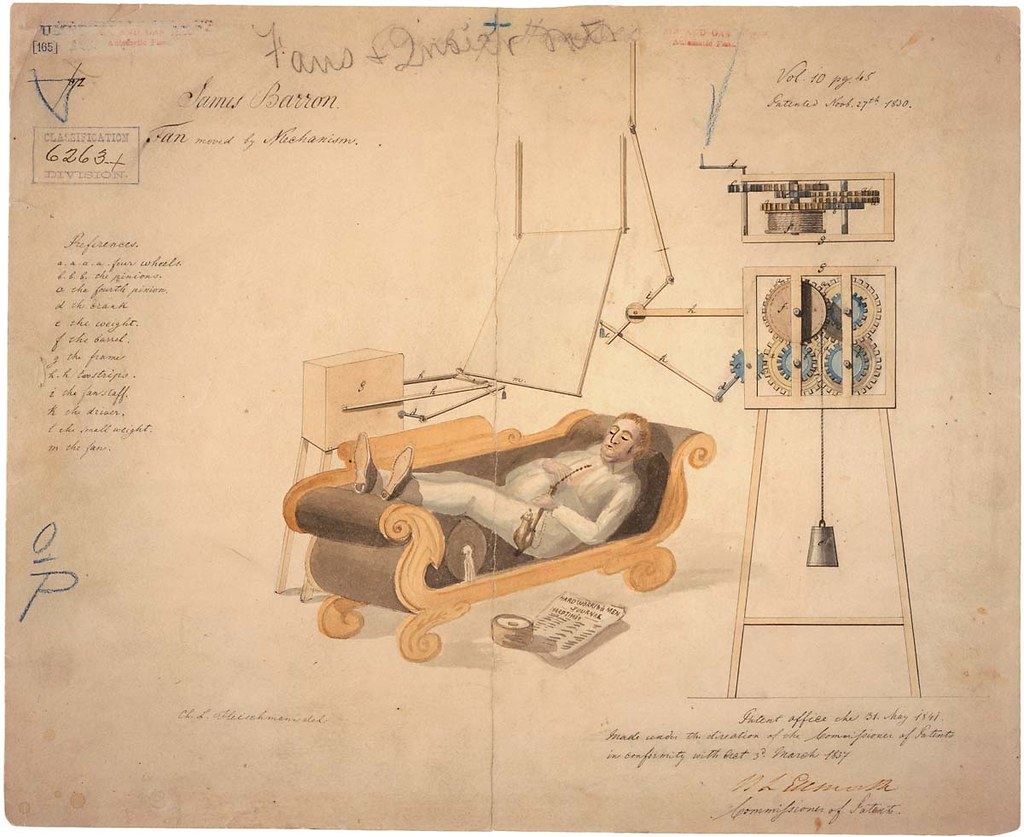

Drawing of Fan Moved by Mechanism: Department of State, Patent Office, 27 November 1830(Cartographic and Architectural Records Section, US National Archives)

Not excepting even the credulous Kraus (see his De Selby's Leben), all the commentators have treated de Selby's disquisitions on night and sleep with considerable reserve. This is hardly to be wondered at since he held (a) that darkness was simply an accretion of 'black air', i.e., a staining of the atmosphere due to volcanic eruptions too fine to be seen with the naked eye and also to certain 'regrettable' industrial activities involving coal-tar by-products and vegetable dyes; and (b) that sleep was simply a succession of fainting-fits brought on by semi-asphyxiation due to (a). Hatchjaw brings forward his rather facile and ever-ready theory of forgery, pointing to certain unfamiliar syntactical constructions in the first part of the third so called 'prosecanto' in Golden Hours. He does not, however, suggest that there is anything spurious in de Selby's equally damaging rhodomontade in the Layman's Atlas where he inveighs savagely against 'the insanitary conditions prevailing everywhere after six o'clock' and makes the famous gaffe that death is merely 'the collapse of the heart from the strain of a lifetime of fits and fainting'. Bassett (in Lux Mundi) has gone to considerable pains to establish the date of these passages and shows that de Selby was hors de combat from his long-standing gall-bladder disorders at least immediately before the passages were composed. One cannot lightly set aside Bassett's formidable table of dates and his corroborative extracts from contemporary newspapers which treat of an unnamed 'elderly man' being assisted into private houses after having fits in the street. For those who wish to hold the balance for themselves, Henderson's Hatchjaw and Bassett is not unuseful. Kraus, usually unscientific and unreliable, is worth reading on this point. (Leben, pp. 17-37.)

As in many other of de Selby's concepts, it is difficult to get to grips with his process of reasoning or to refute his curious conclusions. The 'volcanic eruptions', which we may for convenience compare to the infra-visual activity of such substances as radium, take place usually in the 'evening' are stimulated by the smoke and industrial combustions of the 'day' and are intensified in certain places which may, for the want of a better term, be called 'dark places'. One difficulty is precisely this question of terms. A 'dark place' is dark merely because it is a place where darkness 'germinates' and 'evening' is a time of twilight merely because the 'day' deteriorates owing to the stimulating effect of smuts on the volcanic processes. De Selby makes no attempt to explain why a 'dark place' such as a cellar need be dark and does not define the atmospheric, physical or mineral conditions which must prevail uniformly in all such places if the theory is to stand. The 'only straw offered', to use Bassett's wry phrase, is the statement that 'black air' is highly combustible, enormous masses of it being instantly consumed by the smallest flame, even an electrical luminance isolated in a vacuum. 'This,' Bassett observes, 'seems to be an attempt to protect the theory from the shock it can be dealt by simply striking matches and may be taken as the final proof that the great brain was out of gear.'

A significant feature of the matter is the absence of any authoritative record of those experiments with which de Selby always sought to support his ideas. It is true that Kraus (see below) gives a forty-page account of certain experiments, mostly concerned with attempts to bottle quantities of 'night' and endless sessions in locked and shuttered bedrooms from which bursts of loud hammering could be heard. He explains that the bottling operations were carried out with bottles which were, 'for obvious reasons', made of black glass. Opaque porcelain jars are also stated to have been used, 'with some success'. To use the frigid words of Bassett, such information, it is to be feared, makes little contribution to serious deselbiana (sic).'

Very little is known of Kraus or his life. A brief biographical note appears in the obsolete Bibliographie de de Selby. He is stated to have been born in Ahrensburg, near Hamburg, and to have worked as a young man in the office of his father, who had extensive jam interests in North Germany. He is said to have disappeared completely from human ken after Hatchjaw had been arrested in a Sheephaven hotel following the unmasking of the de Selby letter scandal by The Times, which made scathing references to Kraus's 'discreditable' machinations in Hamburg and clearly suggested his complicity. If it is remembered that these events occurred in the fateful June when the County Album was beginning to appear in fortnightly parts, the significance of the whole affair becomes apparent. The subsequent exoneration of Hatchjaw served only to throw further suspicion on the shadowy Kraus.

Recent research has not thrown much light on Kraus's identity or his ultimate fate. Bassett's posthumous Recollections contains the interesting suggestion that Kraus did not exist at all, the name being one of the pseudonyms adopted by the egregious du Garbandier to further his 'campaign of calumny'. The Leben, however, seems too friendly In tone to encourage such a speculation.

Du Garbandier himself, possibly pretending to confuse the characteristics of the English and French languages, persistently uses 'black hair' for 'black air', and makes extremely elaborate fun of the raven-headed lady of the skies who deluged the world with her tresses every night when retiring.

The wisest course on this question is probably that taken by the little known Swiss writer, Le Clerque. 'This matter,' he says, 'is outside the true province of the conscientious commentator inasmuch as being unable to say aught that is charitable or useful, he must preserve silence.'

Flann O'Brien (Brian O'Nolan) (1911-1966): Chapter VIII, Footnote 1, from The Third Policeman (1939-40), 1967

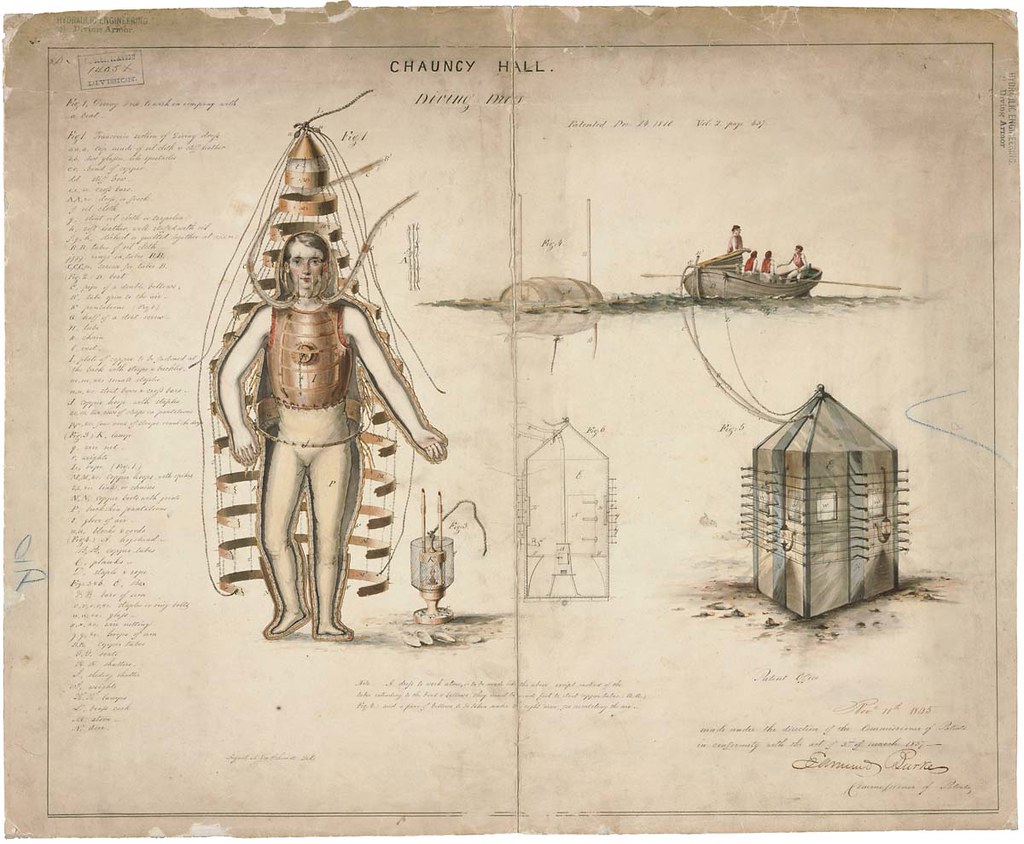

Drawing of Diving Dress: Department of State, Patent Office, 24 December 1810 (Cartographic and Architectural Records Section, US National Archive

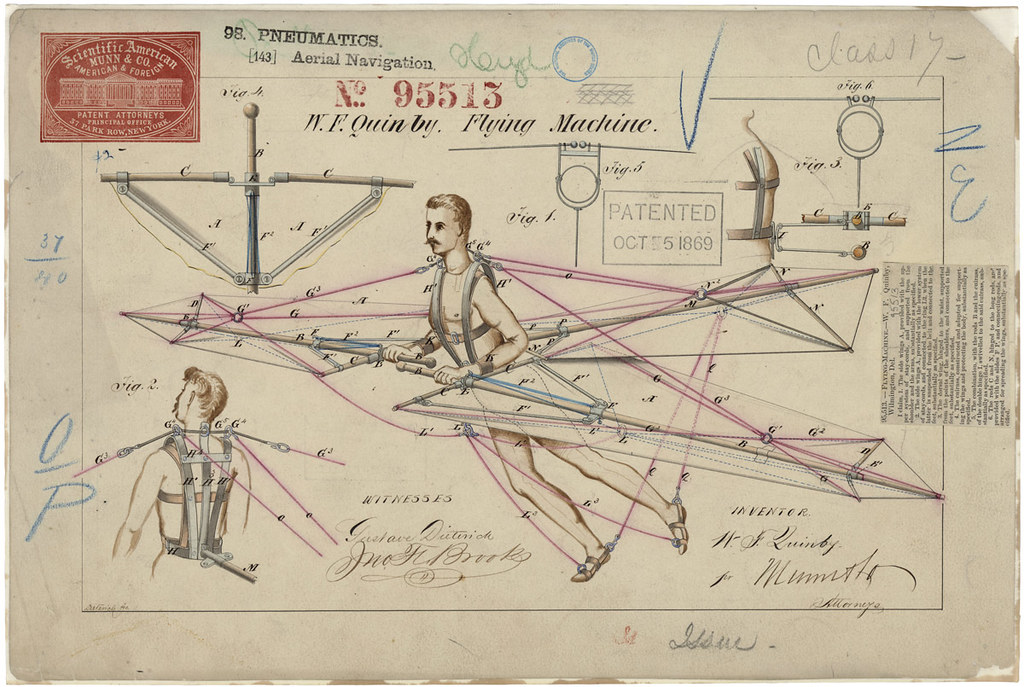

Patent Drawing for a Flying Machine: Department of Commerce, Patent Office, 5 October 1869 (Textual Archives Services Division, US National Archives)

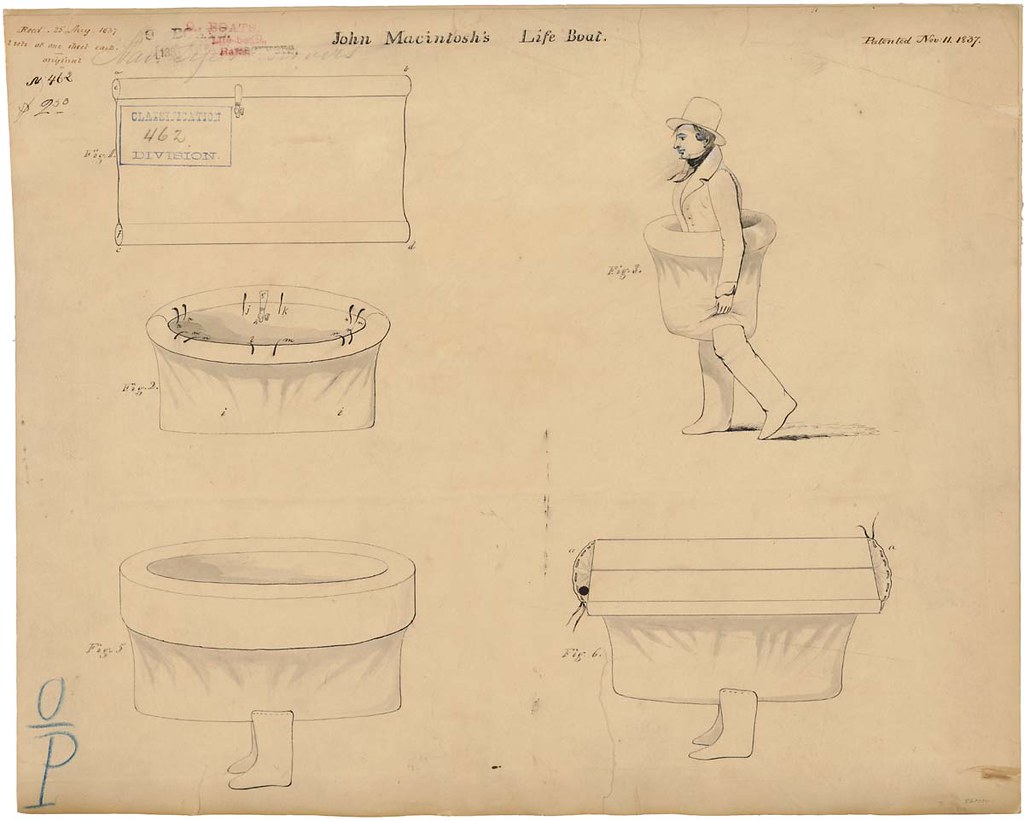

Drawing of a Life Boat: Department of the Interior. Patent Office, 11 November 1837 Cartographic and Architectural Records Section, US National Archives)

Drawing of Creeping Baby Doll: Department of the Interior, Patent Office, 14 March 1871 (Cartographic and Architectural Records Section, US National Archives)

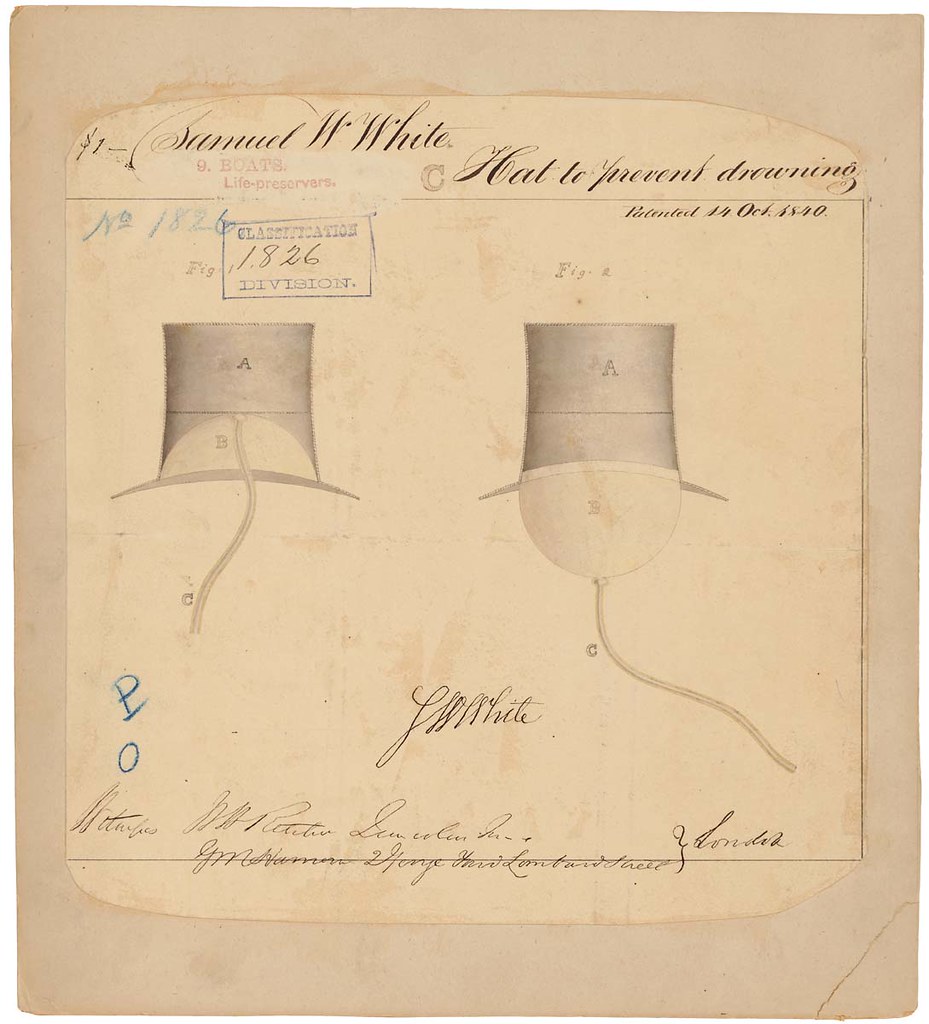

Drawing of Hat to Prevent Drowning: Department of the Interior, Patent Office, 14 October 1840 (Cartographic and Architectural Records Section, US National Archives)

Still Design Patent: Department of State, Patent Office, 1808 (Cartographic and Architectural Records Section, US National Archives)

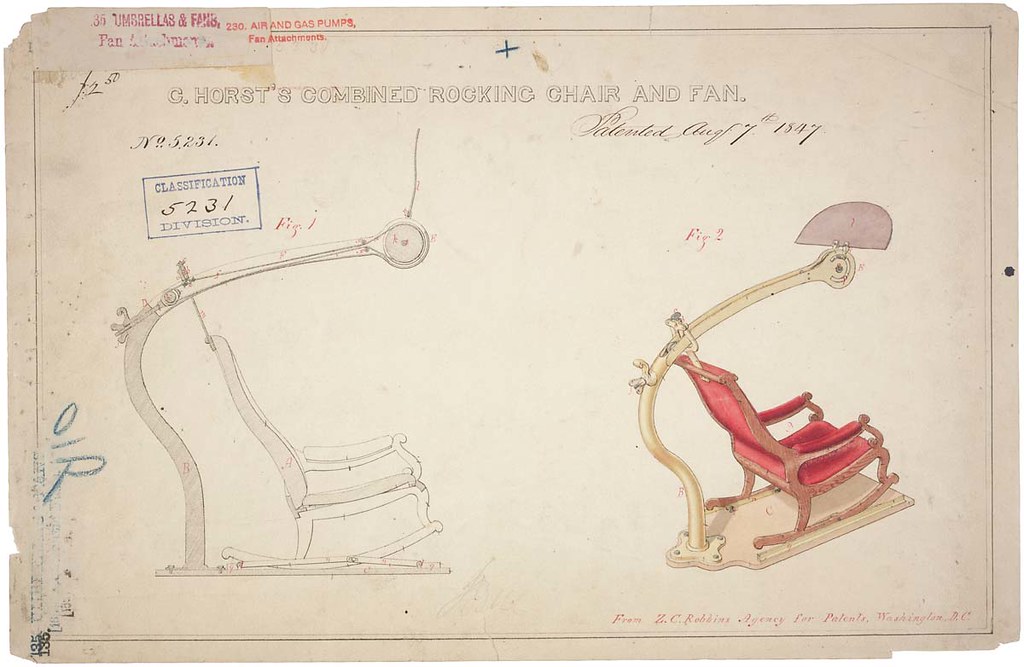

Drawing of Rocking Chair and Fan: Department of the Interior, Patent Office, 7 August 1847 (Cartographic and Architectural Records Section, US National Archives)